Research

Research Interests

Compared to other animals, humans are unique in their linguistic, cognitive, and social abilities. Broadly speaking, our lab explores how these abilities develop and interact in children, as a way of addressing the question of what makes humans special. How do we use language creatively to say things we have never heard before? What can language tell us about how the mind works, and does learning a language influence how we think? How does language depend on the social context in which it is used? These are the types of questions that inspire us. Below are some examples of studies that are currently being conducted in our lab.

Beyond the work we do here in Berkeley, we also occasionally have research trips to India! Our last trip was in December 2023 - January 2024, our second collecting data for the Developing Belief Network! Here are two newsletters detailing some of the work we conducted during our two most recent trips as well!

Check out our virtual library to watch a collection of presentations that our lab members have given about our research!

Ongoing Studies

A pandemic is a decidedly weird time to parent. Life as we know it seems to be shifting, with new changes or considerations sometimes daily. Do these changes affect parents’ and children’s day-to-day routines? In this study, parents fill out a short survey each day for 30-60 days, and also use their phones or tablets to audio-record their child’s bath time routine. We are interested in whether the broader context around families influences these more mundane parts of their lives. For more reflections on the study and parenting during COVID-19 in general, check out bathtubtales.com.

A pandemic is a decidedly weird time to parent. Life as we know it seems to be shifting, with new changes or considerations sometimes daily. Do these changes affect parents’ and children’s day-to-day routines? In this study, parents fill out a short survey each day for 30-60 days, and also use their phones or tablets to audio-record their child’s bath time routine. We are interested in whether the broader context around families influences these more mundane parts of their lives. For more reflections on the study and parenting during COVID-19 in general, check out bathtubtales.com. While we may tend to think of language development as happening through caregiver-child interactions where the caregiver is speaking directly to the child, in many communities, infants’ primary linguistic experience is through overhearing. In this study, we worked with mothers and infants in Chiapas, Mexico to capture infants’ earliest knowledge of words and a specialized system of greetings used in the Tseltal language. Infants are carried in a sling on their mothers’ backs for the first year of life, suggesting that any knowledge they show in our experiments will necessarily be from overhearing their mother’s voice, rather than being taught.

While we may tend to think of language development as happening through caregiver-child interactions where the caregiver is speaking directly to the child, in many communities, infants’ primary linguistic experience is through overhearing. In this study, we worked with mothers and infants in Chiapas, Mexico to capture infants’ earliest knowledge of words and a specialized system of greetings used in the Tseltal language. Infants are carried in a sling on their mothers’ backs for the first year of life, suggesting that any knowledge they show in our experiments will necessarily be from overhearing their mother’s voice, rather than being taught. This study focuses on the ability of children to learn novel words from overheard speech between a speaker and a non-present other. In this study, children are introduced to a set of four objects they’ve never seen before. They are left to explore the objects freely at a table while the experimenter sits off to the side and “works” on her computer without engaging with the child. A short while later, the experimenter’s phone rings, and she feigns a conversation with a friend, casually describing the names and functions of the objects she brought with her. After hanging up, she tests whether the child learned the names and information about the objects from the overheard conversation.

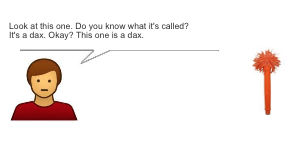

This study focuses on the ability of children to learn novel words from overheard speech between a speaker and a non-present other. In this study, children are introduced to a set of four objects they’ve never seen before. They are left to explore the objects freely at a table while the experimenter sits off to the side and “works” on her computer without engaging with the child. A short while later, the experimenter’s phone rings, and she feigns a conversation with a friend, casually describing the names and functions of the objects she brought with her. After hanging up, she tests whether the child learned the names and information about the objects from the overheard conversation. When engaging in a conversation, we have to monitor which of the words we could use are known by our conversational partner. This is to make sure that he or she understands us properly. Some words, like ‘chair’ or ‘dog’, are likely to be known by almost everyone, whereas others are only familiar to specific groups of people. For example, if you tell your friend that you are going to ‘the city’ and both of you live in the Bay Area, she will probably know that you are talking about San Francisco. A person who is not from here, however, might not understand which city you are talking about. In this study, we teach children new words like ‘dax’ and look at the circumstances under which they think that others will share their new linguistic knowledge.

When engaging in a conversation, we have to monitor which of the words we could use are known by our conversational partner. This is to make sure that he or she understands us properly. Some words, like ‘chair’ or ‘dog’, are likely to be known by almost everyone, whereas others are only familiar to specific groups of people. For example, if you tell your friend that you are going to ‘the city’ and both of you live in the Bay Area, she will probably know that you are talking about San Francisco. A person who is not from here, however, might not understand which city you are talking about. In this study, we teach children new words like ‘dax’ and look at the circumstances under which they think that others will share their new linguistic knowledge. Most of the words that we use are “polysemous”: they carry multiple, related senses of meaning. For example, a word like ‘glass’ could refer to the material (a “glass window”), or an object made from that material (the glasses we drink from or that help us see). Research in our lab aims to understand how children learn such words, and what this reveals about language development more generally. Much research in language development makes use of transcripts of parent-child conversations to understand how parents speak to children and how children begin to use language themselves. However, these transcripts lack information about the specific meanings that words are being used to convey: i.e., when a child uses the word “glass”, are they referring to a material, an object, or something else. In this project, we are annotating transcripts of parent-child conversations to identify the meanings that words are being used with. The outcome of this project will be a new child language database that will help us answer questions about how children are introduced to polysemy in their language environment, and how they learn to use words with multiple meanings.

Most of the words that we use are “polysemous”: they carry multiple, related senses of meaning. For example, a word like ‘glass’ could refer to the material (a “glass window”), or an object made from that material (the glasses we drink from or that help us see). Research in our lab aims to understand how children learn such words, and what this reveals about language development more generally. Much research in language development makes use of transcripts of parent-child conversations to understand how parents speak to children and how children begin to use language themselves. However, these transcripts lack information about the specific meanings that words are being used to convey: i.e., when a child uses the word “glass”, are they referring to a material, an object, or something else. In this project, we are annotating transcripts of parent-child conversations to identify the meanings that words are being used with. The outcome of this project will be a new child language database that will help us answer questions about how children are introduced to polysemy in their language environment, and how they learn to use words with multiple meanings.  Some children grow up in noisy homes with lots going on around them; others grow up in quiet homes with plenty of direct instruction. In this study, we are interested in the ways children might adapt their learning strategies to best meet the demands of their early environments. Using eye-tracking to measure children’s attention in real time, we explore whether kids who grow up in more noisy or chaotic homes develop a more broad attentional style, allowing them to learn from multiple noisy sources at the same time.

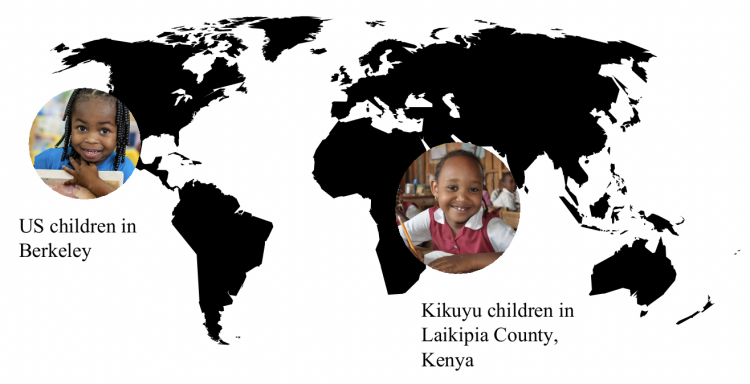

Some children grow up in noisy homes with lots going on around them; others grow up in quiet homes with plenty of direct instruction. In this study, we are interested in the ways children might adapt their learning strategies to best meet the demands of their early environments. Using eye-tracking to measure children’s attention in real time, we explore whether kids who grow up in more noisy or chaotic homes develop a more broad attentional style, allowing them to learn from multiple noisy sources at the same time. Young children often overestimate their knowledge; they think they know more than they actually do. Most prior work attributes children’s overconfidence to cognitive factors. In our study, we test which social factors might lead children to be overconfident. Specifically, we predict that children are more likely to exhibit overconfidence when they believe that this will help them create a positive reputation. For example, children might be particularly overconfident when they think admitting their ignorance would lead others to think they are less smart or intelligent. To test this idea, 4- to 7-year-old children from Berkeley and Kenya are participating in a guessing game, where they have to estimate which color there are more marbles of in a cup. We are interested in how children’s guesses change across age, and how they vary between cultures.

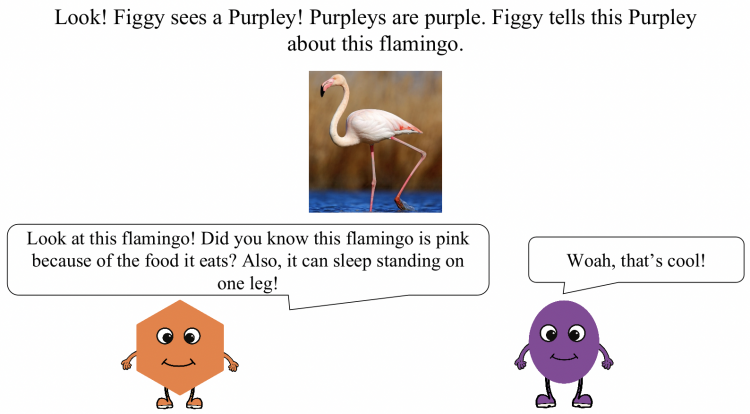

Young children often overestimate their knowledge; they think they know more than they actually do. Most prior work attributes children’s overconfidence to cognitive factors. In our study, we test which social factors might lead children to be overconfident. Specifically, we predict that children are more likely to exhibit overconfidence when they believe that this will help them create a positive reputation. For example, children might be particularly overconfident when they think admitting their ignorance would lead others to think they are less smart or intelligent. To test this idea, 4- to 7-year-old children from Berkeley and Kenya are participating in a guessing game, where they have to estimate which color there are more marbles of in a cup. We are interested in how children’s guesses change across age, and how they vary between cultures. Every speaker belongs to a potentially infinite set of non-mutually exclusive groups that can influence what they say and how they say it. For example, someone can be an American, a Californian, a Bay Area resident, and a Berkeley student as well as a Star Trek fan who loves model trains, is an amateur ornithologist, and dabbles in semi-professional DJing. As listeners, we can use our knowledge of speakers to form expectations about what we will hear. If you were talking to the aforementioned person, you would be surprised if they, an American Star Trek fan, started speaking with a French accent or mistakenly referred to Star Trek as Star Wars. How do children (and adults) learn what cues are useful in predicting a speaker’s likely utterances? Further, how and when do children use these cues to organize speakers into different groups? And how do they use their knowledge of these groups to predict and interpret what they hear?

Every speaker belongs to a potentially infinite set of non-mutually exclusive groups that can influence what they say and how they say it. For example, someone can be an American, a Californian, a Bay Area resident, and a Berkeley student as well as a Star Trek fan who loves model trains, is an amateur ornithologist, and dabbles in semi-professional DJing. As listeners, we can use our knowledge of speakers to form expectations about what we will hear. If you were talking to the aforementioned person, you would be surprised if they, an American Star Trek fan, started speaking with a French accent or mistakenly referred to Star Trek as Star Wars. How do children (and adults) learn what cues are useful in predicting a speaker’s likely utterances? Further, how and when do children use these cues to organize speakers into different groups? And how do they use their knowledge of these groups to predict and interpret what they hear? In this project, we aim to study whether previous experience with an ambiguous word (polysemous, homonymous or homophonous) influences how children interpret that word. Ambiguity is a very common phenomena in language. Actually, most open-class words we normally use are ambiguous: they are associated with several interpretations. Previous research has shown that adults’ interpretation of words is very malleable and can change depending on previous experience. However, the mechanism underlying this effect remains unclear, and there is not much knowledge about whether this effect may influence children’s interpretation of ambiguous words.

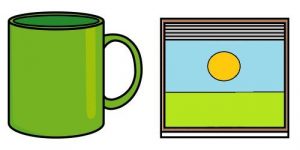

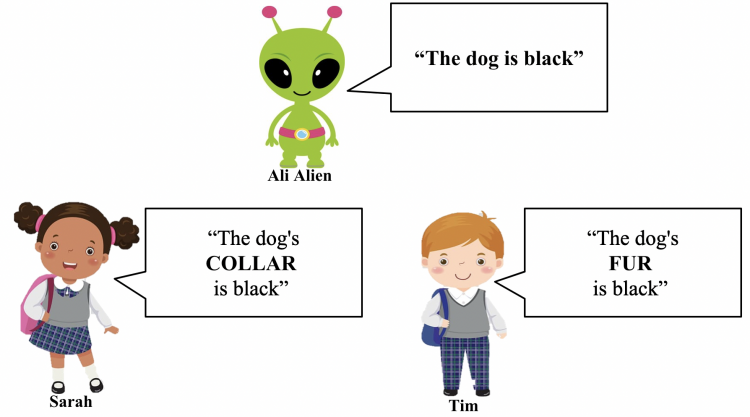

In this project, we aim to study whether previous experience with an ambiguous word (polysemous, homonymous or homophonous) influences how children interpret that word. Ambiguity is a very common phenomena in language. Actually, most open-class words we normally use are ambiguous: they are associated with several interpretations. Previous research has shown that adults’ interpretation of words is very malleable and can change depending on previous experience. However, the mechanism underlying this effect remains unclear, and there is not much knowledge about whether this effect may influence children’s interpretation of ambiguous words. We propose that each human concept (e.g., kitchen) has some core properties which capture the meaning of that concept (e.g., having a place to cook, and having cooking equipment, such as an oven). These core properties are distinguished from properties which are common, but not part of the core meaning of the concept (e.g., having a clock, for a kitchen). We are currently exploring whether 4-6 year old children prefer to interpret sentences with respect to these core properties. For example, in this study children hear sentences such as “The kitchen is new,” and they are asked whether that means that the kitchen’s oven is new, or whether it means that the kitchen’s clock is new. Since most sentences in natural language are ambiguous, this work may shed light on a crucial constraint which helps children converge on specific meanings for the sentences they hear as they come to master their language.

We propose that each human concept (e.g., kitchen) has some core properties which capture the meaning of that concept (e.g., having a place to cook, and having cooking equipment, such as an oven). These core properties are distinguished from properties which are common, but not part of the core meaning of the concept (e.g., having a clock, for a kitchen). We are currently exploring whether 4-6 year old children prefer to interpret sentences with respect to these core properties. For example, in this study children hear sentences such as “The kitchen is new,” and they are asked whether that means that the kitchen’s oven is new, or whether it means that the kitchen’s clock is new. Since most sentences in natural language are ambiguous, this work may shed light on a crucial constraint which helps children converge on specific meanings for the sentences they hear as they come to master their language. Children endorse stereotypes about competence from an early age. For example, by the time children are 6, they already associate brilliance with males more than females. These stereotypes are particularly harmful as they influence how people are treated and can shape educational and career outcomes.

Children endorse stereotypes about competence from an early age. For example, by the time children are 6, they already associate brilliance with males more than females. These stereotypes are particularly harmful as they influence how people are treated and can shape educational and career outcomes.

In the current project, we investigate how stereotypes about competence develop, focusing on linguistic interactions as a candidate mechanism. We ask if children are sensitive to variations in how a speaker talks to different social groups—specifically, whether they explain facts that are obvious or interesting— and whether this variation leads children to make inferences about the social groups’ competence.

This project is focused on better understanding people’s financial situation affects them and their children in the East Bay. This study will help to support future research that can alleviate financial strain. This project will involve participants 1) completing short online surveys about their financial situation and health and 2) making audio recordings of the sound environment around their child.

This project is focused on better understanding people’s financial situation affects them and their children in the East Bay. This study will help to support future research that can alleviate financial strain. This project will involve participants 1) completing short online surveys about their financial situation and health and 2) making audio recordings of the sound environment around their child.Completed Studies

A feature of languages, such as English, is the ability to use a single word in multiple related ways. For example, the word “glass” can refer to the material “glass” and can also refer to “a glass” that one can

A feature of languages, such as English, is the ability to use a single word in multiple related ways. For example, the word “glass” can refer to the material “glass” and can also refer to “a glass” that one candrink out of. Our study explores whether children use this relationship between word meanings to structure their understanding of a new word and object categories. Children are introduced to a novel material (some “dax”) and a new object that either shares the material name (a “dax”) or does not (a “wug”). We explore whether sharing the material name leads children to categorize the object with other objects made from the same material, and whether knowledge of the relationship between word meanings help children remember the meaning of novel words.

Preschool aged children encounter a lot of different rules regarding how one ought to behave. This study explores how children begin to distinguish between moral norms (which concern the welfare of others) and arbitrary norms (like what is an appropriate outfit for school). Children play a game with a puppet “Max” who breaks an explicit rule. We explore the level to which children judge Max’s actions to be wrong, and whether they consider Max’s knowledge (or lack of knowledge) about the rule when deciding how bad Max’s action is. So far, we’ve found that preschoolers judge Max’s rule breaking as worse when he breaks a moral rule than when he breaks an arbitrary rule.

Preschool aged children encounter a lot of different rules regarding how one ought to behave. This study explores how children begin to distinguish between moral norms (which concern the welfare of others) and arbitrary norms (like what is an appropriate outfit for school). Children play a game with a puppet “Max” who breaks an explicit rule. We explore the level to which children judge Max’s actions to be wrong, and whether they consider Max’s knowledge (or lack of knowledge) about the rule when deciding how bad Max’s action is. So far, we’ve found that preschoolers judge Max’s rule breaking as worse when he breaks a moral rule than when he breaks an arbitrary rule.  Children often find themselves in disagreement with others. Intuitively, one might think of disagreement as having primarily negative consequences. In our study, however, we test the idea that disagreement can have important positive effects on children’s cognition. Previous work has shown that children often think they know more than they actually do; they show systematic overconfidence. We investigate whether experiencing disagreement with another person can cause children to “take a step back” from their belief and develop a more realistic view of their intellectual limitations. In our study, children play a fun detective game in which they have to find out which toys make a machine play music. They play the game together with a researcher who sometimes agrees with them, and sometimes disagrees about which toys make the machine go. We are interested in finding out whether this affects how sure children are that they found the right solution and whether children who experience disagreement are more motivated to search for additional information about the problem at hand when given the option.

Children often find themselves in disagreement with others. Intuitively, one might think of disagreement as having primarily negative consequences. In our study, however, we test the idea that disagreement can have important positive effects on children’s cognition. Previous work has shown that children often think they know more than they actually do; they show systematic overconfidence. We investigate whether experiencing disagreement with another person can cause children to “take a step back” from their belief and develop a more realistic view of their intellectual limitations. In our study, children play a fun detective game in which they have to find out which toys make a machine play music. They play the game together with a researcher who sometimes agrees with them, and sometimes disagrees about which toys make the machine go. We are interested in finding out whether this affects how sure children are that they found the right solution and whether children who experience disagreement are more motivated to search for additional information about the problem at hand when given the option.  The meanings of a lot of words are context-dependent. For example, listeners judge “a lot of crumbs” to be more than “a lot of mountains.” Further, an important part of the context in this case is the specific person saying the words. In this study, we look specifically at how children think about quantifiers (words like some, many, a lot, all, none, etc.). We present children with various proportions and ask which words they think best describe the proportion. During the preschool years, children are learning how to use information about the context of a statement to figure out what the statement means. Our study is trying to see if children understand that the person producing the statement is a very important part of understanding what was meant.

The meanings of a lot of words are context-dependent. For example, listeners judge “a lot of crumbs” to be more than “a lot of mountains.” Further, an important part of the context in this case is the specific person saying the words. In this study, we look specifically at how children think about quantifiers (words like some, many, a lot, all, none, etc.). We present children with various proportions and ask which words they think best describe the proportion. During the preschool years, children are learning how to use information about the context of a statement to figure out what the statement means. Our study is trying to see if children understand that the person producing the statement is a very important part of understanding what was meant. A healthy public discourse requires that people respond to disagreement in reasonable ways. For example, we should update our beliefs when others have better evidence for an alternative view. We investigate children’s developing ability to selectively adjust their beliefs when confronted with a disagreeing peer. In a fun searching-game, children formed an initial belief about where a bunny went and are then confronted with the opposing belief of a disagreeing other person. We are interested in whether children adjust their beliefs based on which of the two beliefs is supported by more evidence. So far, we find that already very young children (4 to 6 years) respond reasonably to many disagreements. Interestingly, however, they do not yet demonstrate the “intellectually virtuous” ability to suspend judgment when two beliefs are supported by an equal amount of evidence. In our current study, we are trying to understand why this might be the case.

A healthy public discourse requires that people respond to disagreement in reasonable ways. For example, we should update our beliefs when others have better evidence for an alternative view. We investigate children’s developing ability to selectively adjust their beliefs when confronted with a disagreeing peer. In a fun searching-game, children formed an initial belief about where a bunny went and are then confronted with the opposing belief of a disagreeing other person. We are interested in whether children adjust their beliefs based on which of the two beliefs is supported by more evidence. So far, we find that already very young children (4 to 6 years) respond reasonably to many disagreements. Interestingly, however, they do not yet demonstrate the “intellectually virtuous” ability to suspend judgment when two beliefs are supported by an equal amount of evidence. In our current study, we are trying to understand why this might be the case. While we may talk about ‘math’ as if it were a universally well-defined subject, different people have different conceptions of what counts as ‘math,’ which we’ve already observed with adults, young children, and middle school-aged children in India. In this study, students will sort a variety of activities according to whether or not they believe these activities ‘involve math.’ We are interested in how individuals’ definitions of ‘math’ may relate to their willingness to approach activities in the world that explicitly involve math.

While we may talk about ‘math’ as if it were a universally well-defined subject, different people have different conceptions of what counts as ‘math,’ which we’ve already observed with adults, young children, and middle school-aged children in India. In this study, students will sort a variety of activities according to whether or not they believe these activities ‘involve math.’ We are interested in how individuals’ definitions of ‘math’ may relate to their willingness to approach activities in the world that explicitly involve math. This study researches the development of children’s ability to map epistemic modal verbs (i.e. verbs like can and should that indicate a speaker’s beliefs about events in the world) to probabilistic situations and what the nature of this mapping is. Comparable research done with adults has found people tend to have categorical as opposed to continuous representations of these verbs in relation to the likelihood of events. That is, adults group “strong” modals (e.g., will, must, or should) together and “weak” modals (e.g., might, may, could) together. Interestingly, adults don’t see any difference within these groups. That is, they see events that “will happen” as being just as likely as events that “should happen.” In our research with adults, strong modals were chosen more often when shown high probability events (e.g., 90% probability) and weak modals were chosen more often when shown low probability events (e.g., 10% probability). Given that young children are also developing an understanding of probability and inference skills, the simultaneous development of an understanding of modal verbs is expected to help support these other skills in complex ways. While the question of how children think about modals will hopefully be informed, the current focus is establishing what understanding of these words exists at each age, as there has been little work on this so far.

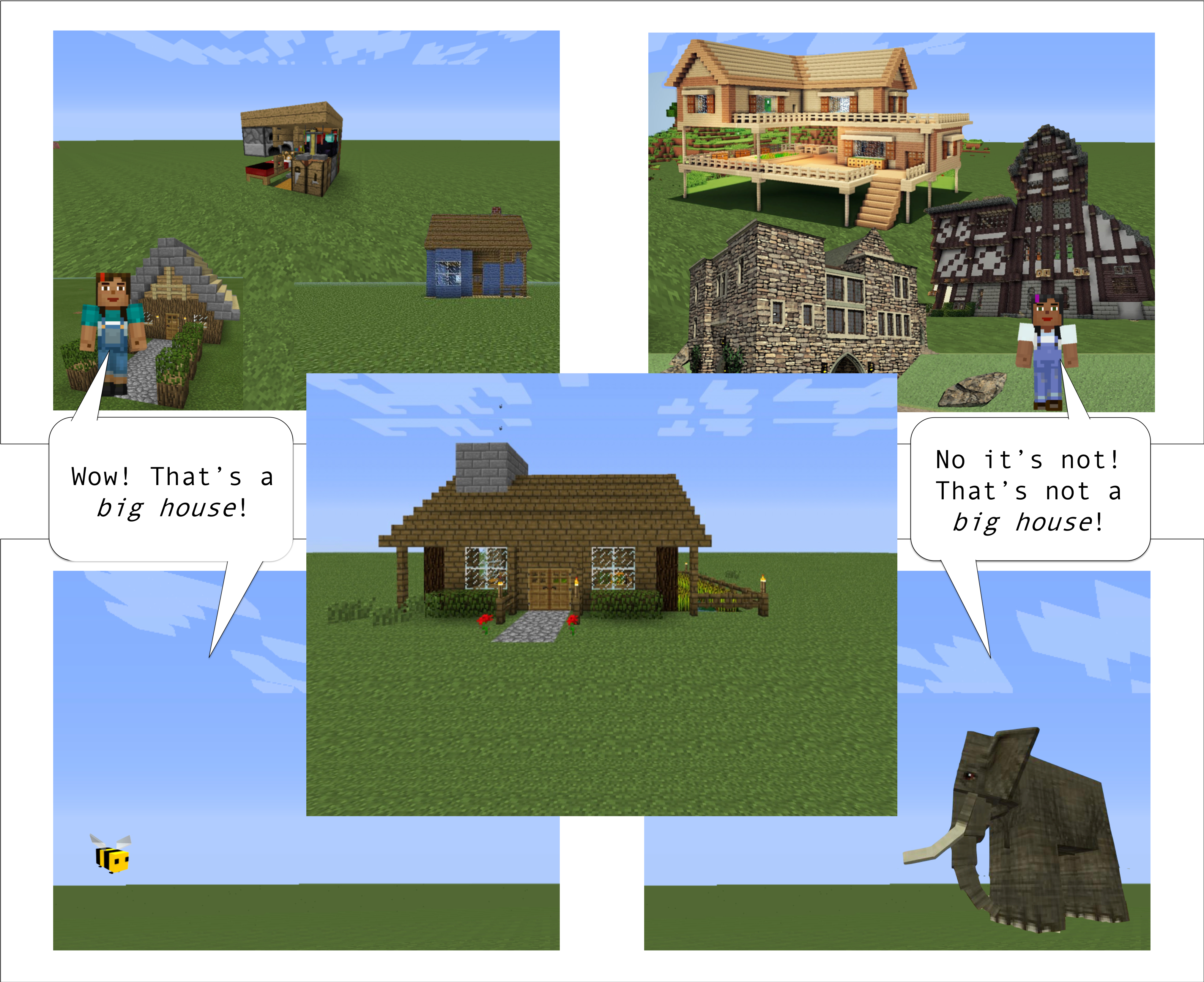

This study researches the development of children’s ability to map epistemic modal verbs (i.e. verbs like can and should that indicate a speaker’s beliefs about events in the world) to probabilistic situations and what the nature of this mapping is. Comparable research done with adults has found people tend to have categorical as opposed to continuous representations of these verbs in relation to the likelihood of events. That is, adults group “strong” modals (e.g., will, must, or should) together and “weak” modals (e.g., might, may, could) together. Interestingly, adults don’t see any difference within these groups. That is, they see events that “will happen” as being just as likely as events that “should happen.” In our research with adults, strong modals were chosen more often when shown high probability events (e.g., 90% probability) and weak modals were chosen more often when shown low probability events (e.g., 10% probability). Given that young children are also developing an understanding of probability and inference skills, the simultaneous development of an understanding of modal verbs is expected to help support these other skills in complex ways. While the question of how children think about modals will hopefully be informed, the current focus is establishing what understanding of these words exists at each age, as there has been little work on this so far. Are some explanations for disagreements over things like beauty or taste more accessible to children than others? In this study, we explore children’s intuitions about when it is okay for two speakers to disagree, contrasting cases where the speakers have had divergent personal experiences (e.g., disagreeing over whether a house is “big” when one speaker has grown up around cottages, and the other around mansions), versus cases where the speakers have intrinsically different perspectives (e.g., disagreeing over “big” when one speaker is a bumblebee and the other an elephant).

Are some explanations for disagreements over things like beauty or taste more accessible to children than others? In this study, we explore children’s intuitions about when it is okay for two speakers to disagree, contrasting cases where the speakers have had divergent personal experiences (e.g., disagreeing over whether a house is “big” when one speaker has grown up around cottages, and the other around mansions), versus cases where the speakers have intrinsically different perspectives (e.g., disagreeing over “big” when one speaker is a bumblebee and the other an elephant).

Our study looks at the strategies children use to think about the world around them–how they locate objects in space, relative to themselves and to landmarks and cues nearby. In the study, children play a memory game where they study the locations of toys and then recreate the scene they studied after a short delay. We’re interested in what strategies children use to remember the toys’ locations, and how these strategies change over development.